2012

Founder Brian Booth Passes Away

When Brian Booth was once asked where he found the time to nurture, or rescue, so many of his homeland’s writers and institutions, he said: “I love Oregon. And that was always on my plate.”

At the end of Booth’s extraordinary life – he died early Wednesday of cancer at age 75 – one hardly knows where to begin in transcribing the difference that made.

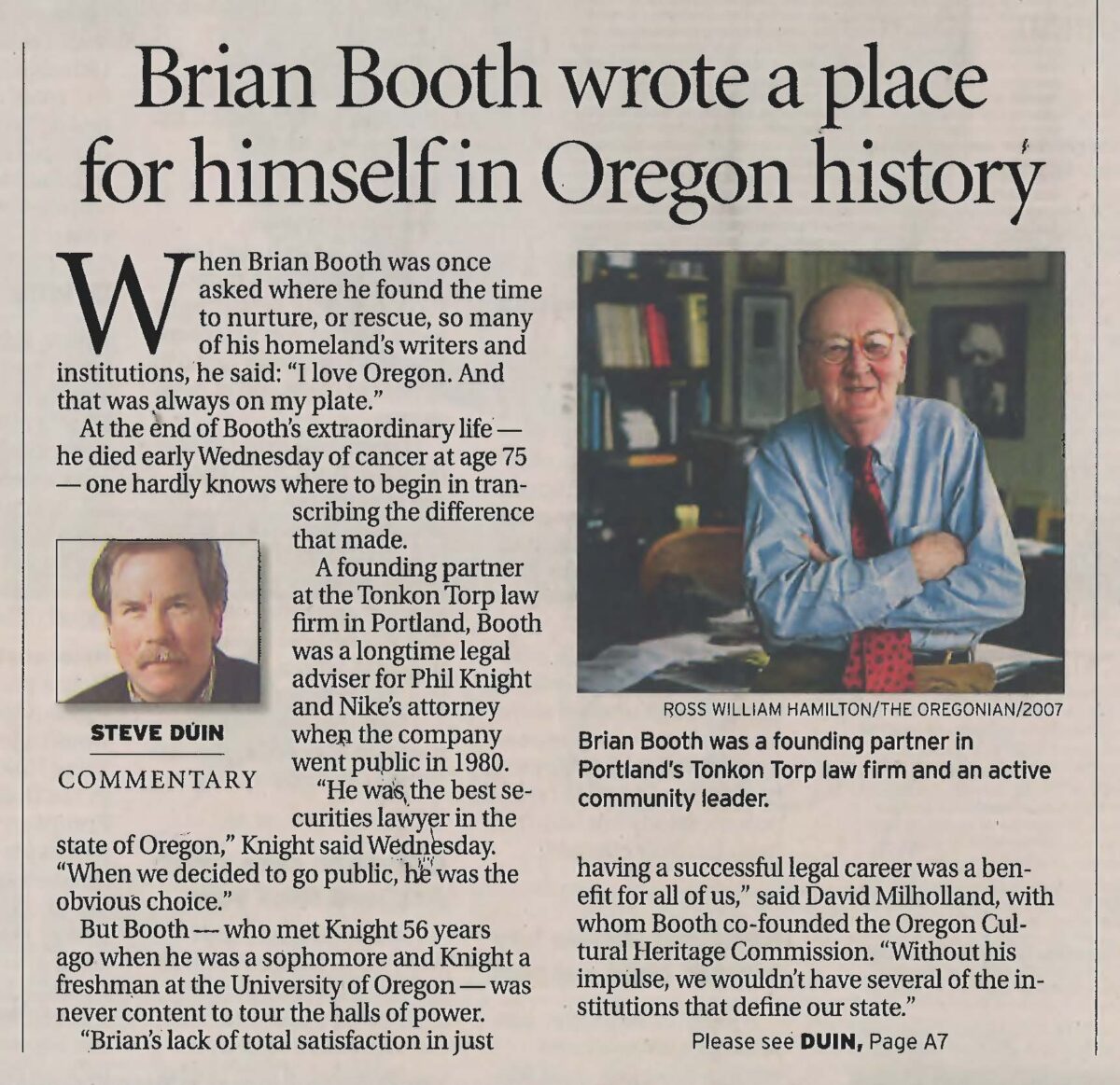

A founding partner at the Tonkon Torp law firm in Portland, Booth was a longtime legal adviser for Phil Knight and Nike’s attorney when the company went public in 1980.

“He was the best securities lawyer in the state of Oregon,” Knight said Wednesday. “When we decided to go public, he was the obvious choice.”

But Booth – who met Knight 56 years ago when he was a sophomore and Knight a freshman at the University of Oregon – was never content to tour the halls of power.

“Brian’s lack of total satisfaction in just having a successful legal career was a benefit for all of us,” said David Milholland, with whom Booth co-founded the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission. “Without his impulse, we wouldn’t have several of the institutions that define our state.”

Booth founded Literary Arts in 1986 and – with his wife, Gwyneth Gamble Booth, at his side – created the Oregon Book Awards and Oregon Literary Fellowships. “It was very important to him that he was an Oregonians,” said Ursula Le Guin, a legendary science-fiction and fantasy writer, “and this was an Oregon book award.”

“He did more to resurrect the idea of Oregon literature than anyone I can think of,” added Brian Doyle, author of “Mink River.” “He was intent that remember the great storytellers…and absolutely committed to how we are stories, to how stories are the food of a place.”

A devoted collector of rare books, Booth rescued writers such as H.L. Davis and Stewart Holbrook from dusty obscurity, memorialized the latter in his 1994 book, “Wildmen, Wobblies and Whistle Punks: Stewart Holbrook’s Lowbrow Northwest.

Booth was the first chairman of the Oregon Parks Commission and instrumental in the success of the Knight Cancer Center at Oregon Health & Science University.

He guided the boards of the Portland Art Museum, the OHSU Foundation and the University of Oregon Art Museum through tumultuous and dynamic periods in their histories. And he once put pianist Thomas Lauderdale to work researching out-of-print Oregon writers until Lauderdale could find the inspiration for Pink Martini.

“Brian loved his corporate power, but he never gave up on the literary, artistic wild side of life,” said poet Walt Curtis. “He loved the outsiders and the lowbrow loggers. He was always on our side.

”Brian Booth is the greatest guy I’ve ever met.”

Booth grew up in Roseburg, graduating from the University of Oregon in 1958 and – after a stint in the Army – gaining his law degree from Stanford in 1962.

He is survived by his wife of 27 years, Gwyneth; son, Thomas Booth; daughter, Jennifer Booth; stepsons, Theodore and Brian Gamble; stepdaughter, Elizabeth Caldwell; sister, Harriet Scofield…

And countless admirers, who were forever struck by Booth’s grace, humor and humility.

“You could put him in any room, anywhere, and after awhile the blowhards would quiet down and listen to him,” said Bart Eberwein, the executive vice president at Hoffman Construction.

“He had the ability to be really smart and really human. You would learn and you wouldn’t feel stupid for having to learn.”

“Most of all, I’ll miss his friendship,” Knight said. “The state of Oregon has lost a giant.”

Booth was diagnosed with melanoma in his 60s and survived several early turns with the skin cancer.

Three and a half weeks ago, Gwyneth Gamble Booth said, she and her husband were walking their Scottie on the beach at Neskowin. Then the melanoma returned with a quiet rage.

Weakened by the radiation treatments, Booth moved over the weekend into a hospital bed set up in the living room of his West Hills home.

On Wednesday, just after midnight, Gamble Booth said, “I crawled into that hospital bed with him and just had a chance to tell him how much fun we had together.”

“He turned to me and his mouth closed. He had this quirky smile, this ‘I have a joke and I can’t wait to tell you’ smile. He gave me that smile and died.”

He died, as he lived, believing he was still in debt to the state that inspired his ancestors, his literary heroes, and his curiosity.

“What kept him here? What drove him to give so much of himself to Oregon?” Eberwein said.

“I think it’s something in the soil. Not every tree grows in it, but it made him tower. And it needs to be amplified, cherished and taken care of, so other people can put their roots down in it.”

This article (by Steve Duin) is the property of Oregonian Publishing Co. Photo (by Ross William Hamilton) courtesy of The Oregonian.